When you think “vessel” and “neck,” what words come to mind? For me, the first two words I think of are carotid and jugular. I’ve heard these words used in the vernacular every so often, especially the latter. If someone wants to convey a sentiment of “going for the kill” or delivering a coup de grace, that person can say he or she is “going for the jugular.” Let’s start with this one:

Jugular

Origin: Latin, jugulum (throat)

Named for the fact the jugular veins are near the throat

There are two jugular veins, one external and one internal on each side of the body. The internal jugular is covered by the sternocleidomastodeus muscle, while the external one is readily visible. These two veins are extremely important because they drain the deoxygenated blood from the head back to the superior vena cava.

What about the other vessel(s) of interest? There is a common carotid artery on both sides of the body, and this artery branches into the internal and external carotid arteries. The former supplies blood to the brain, while the latter supplies blood to the face and head. The etymology is rather interesting:

Carotid

Origin: Greek, karos (stupor)

So called from Galen’s observation that their compression causes stupor/somnolence

If one were to bilaterally massage both carotid sinuses (the point at which the common carotid bifurcates), the baroreceptors of the sinus are fooled into thinking there is a higher-than-normal blood pressure. To compensate, the blood pressure decreases, resulting in a sensation of stupor. Interestingly enough, there is a therapeutic use for this maneuver: the alleviation of supraventricular tachycardia:

Supraventricular tachycardia

Origin: Latin, supra– (above) + ventricle (chamber of the heart; translates to belly, for the ventricles comprise the “belly” of the heart)

Origin: Greek, tachys (swift) + kardia (heart)

A fast pulse due to improper electrical activity above the level of the ventricles

What other afflictions could these vessels suffer from? One thing that can go wrong with the carotid artery is carotid artery stenosis:

Stenosis

Origin: Greek, stenos (narrow/close) + -osis

Condition of narrowness, taken to mean a narrowing

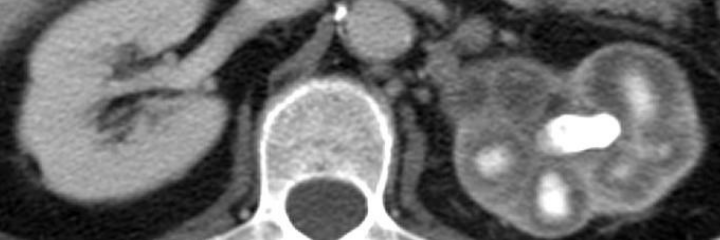

Carotid artery stenosis is oftentimes caused by atherosclerosis, or the reduction of the interior arterial (luminal) diameter due to the accumulation of gunk. This gunk is a lovely mixture of dead cells, cholesterol, and fats.

Atherosclerosis

Origin: Greek, athres (gruel) + sklerein (to harden) + –osis

Condition of the hardening of gruel

Sounds delicious!