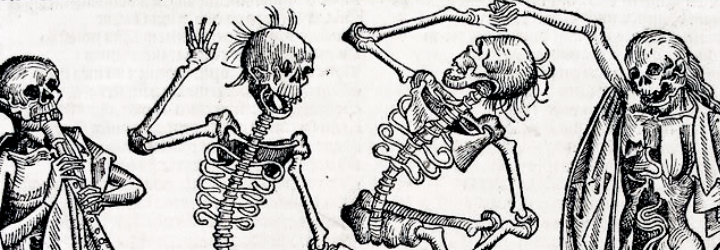

Death and disease were commonplace during medieval times, and this is perhaps best exemplified by the Black Death—an instantiation of bubonic plague that ravaged Europe between 1347 and 1353. To give a quick background on the Black Death: early in the fourteenth century, a Gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis spread via Mongol horsemen and environmental factors from the Gobi Desert (in China) to India, the Middle East, and finally to the Mediterranean Basin. Late in 1347, the Black Death had reached Italian port cities such as Genoa and then traveled across Europe. While the worst of the plague had subsided by 1350, it had killed millions of people during its short tenure in Europe.

Bubonic

Origin: Latin, bubo (pustule, growth, swelling); from Greek boubon (groin)

An inflamed swelling of a lymph node, especially in the armpit or groin

Plague

Latin, plaga (stripe/wound)

The pestilent disease caused by the virulent bacterium Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis

Origin: Latin, pestis (plague/pestilence)

Yersinia: named after its discoverer Alexandre Yersin, a Swiss/French physician

Characterized by delirium, chills, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and the formation of buboes, plague is often fatal when untreated. This is exemplified by the 30 to 50 percent mortality rate observed during the Black Death. Medieval physicians found themselves at a loss to explain what caused the plague, how it was transmitted, and why certain individuals survived while others perished. Despite the lack of information, the plague was largely perceived as contagious via “bad smells” through the miasmatic [Origin: Greek, miasma (stain, pollution)] theory of disease. Though not a form of treatment, the best recommendation for dealing with plague at the time came from the wisdom of Galen and Hippocrates: “Cito, longe, tarde” (Latin: [leave] immediately, to a great distance, for a long time). For the unlucky individuals infected with plague, both patients and physicians made frantic attempts to cure the disease. These “treatments” included:

- Consuming arsenic, crushed emeralds, or rotten treacle (uncrystallized syrup)

- Our personal recommendation: blood-letting

- Introduction of “good smells” to replace the bad ones via herbs and posies

- Sitting in the sewers to practice self-flagellation.

Self-Flagellation

Origin: Latin, flagellum (whip, lash, scourge)

Hitting oneself with a whip, usually as part of a religious ritual

While it is commonly known as the bubonic plague, several forms of plague existed during the Black Death including pneumonic and septicaemic forms. These different classifications are defined by the bodily location of the affliction.

Pneumonic

Origin: Greek, pneumon (lung) + -ikos (pertaining to)

Pertaining to the lungs

Septicaemic

Origin: Greek, septein (to make rotten) + haima (blood)

Invasion and persistence of bacteria in the bloodstream

While plague is much less common in the modern era, it continues to affect about 5,000 people annually throughout the world. The prognosis today is much better than it once was, given that modern physicians possess an arsenal of antibiotics, e.g., streptomycin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and sulfonamide.